Scotch and Bourbon: The Essential and the Essence

|

|

Time to read 4 min

|

|

Time to read 4 min

Scotches and Bourbons are cheerful kin, but there are some distinct differences in their full bloodlines.

This article will review some of their geographic, distillation, and taste distinctions, and set you up at the bar with more than a wee dram of spirits knowledge.

Let’s get the spelling thing out of the way right off:

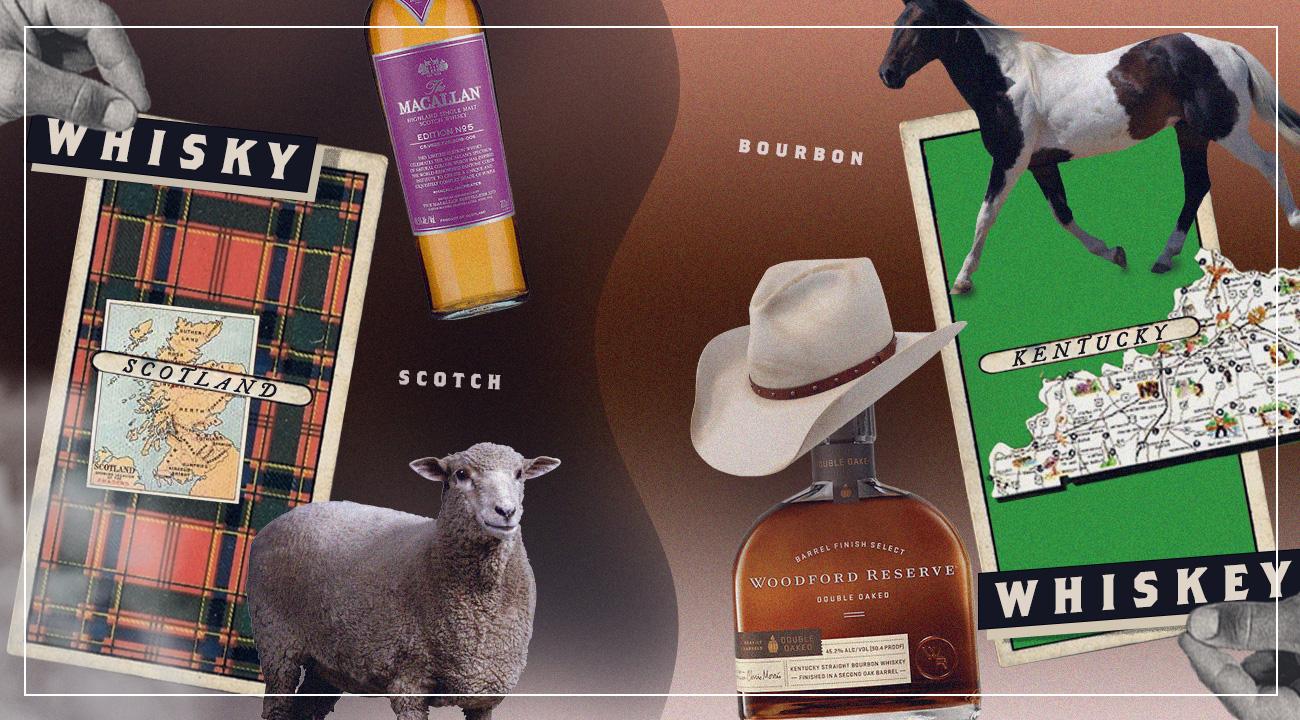

In Scotland, and much of the rest of the world, their grain-based spirits are Whisky.

In the U.S. and Ireland, they pour the good stuff from a bottle labeled Whiskey. Scotch and Bourbon are both Whiskies, with more than the mere geographical distance between the two.

But do scan the map for a moment: Scotch isn’t Scotch unless it’s made in Scotland. They’ve been barreling that stuff for many hundreds of years, much longer than that cheeky-youth Bourbon, long associated with early Kentucky roots, but now distilled widely across the states.

For both Whiskies, there are many regulatory statutes that specify the particulars of what must go from farmer’s field to fermentation, from distillation to barrel to bottle—let’s look at the most significant:

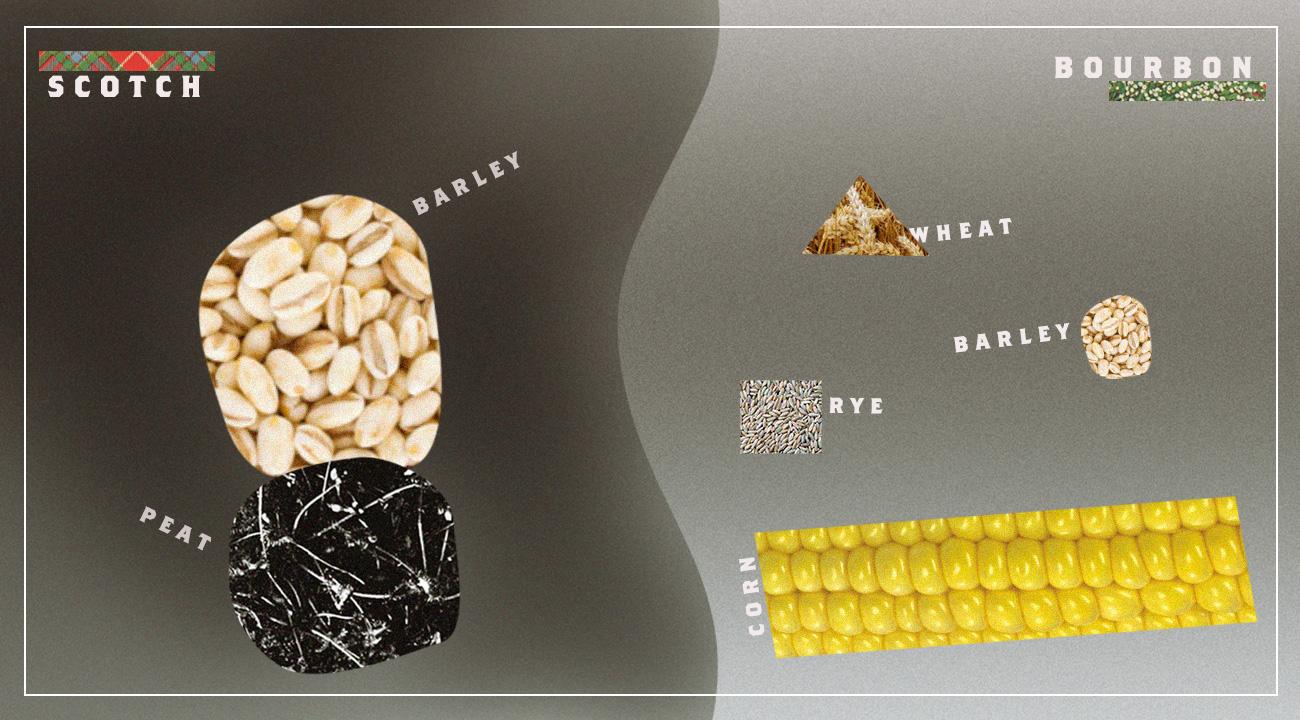

Bourbon begins with corn. Specifically, the grain mixture, the mash, must have at minimum 51 percent corn. From there, distillers use varied percentages of more corn, rye, wheat, barley, and sometimes more esoteric grains to spice, sweeten, soften and refine the flavor profile of Bourbon.

Scotch sets its standards on malted barley as its primary constituent. A single-malt Scotch gets its “single” from being the product of a single distillery—that distillery can combine batches and barrels from differing distillations and it’s still single malt.

The grain remains exclusively barley. Single-grain Scotches again are the products of a single distillery but can combine other grains, which seems confusing at first glance. We’ll get to blends (another Scotch category) later, so your brows won’t furrow all the more at this moment.

The barley at the heart of many—though not all—Scotches isn’t merely malted (germinated); it’s peated as well. That process involves burning the peat soil beneath the pre-distilled malt to smoke in an earthy character that invigorates many a Whisky.

Both Scotches and Bourbons introduce some yeast into their mash to gobble those starches and release the sugars integral to distilling.

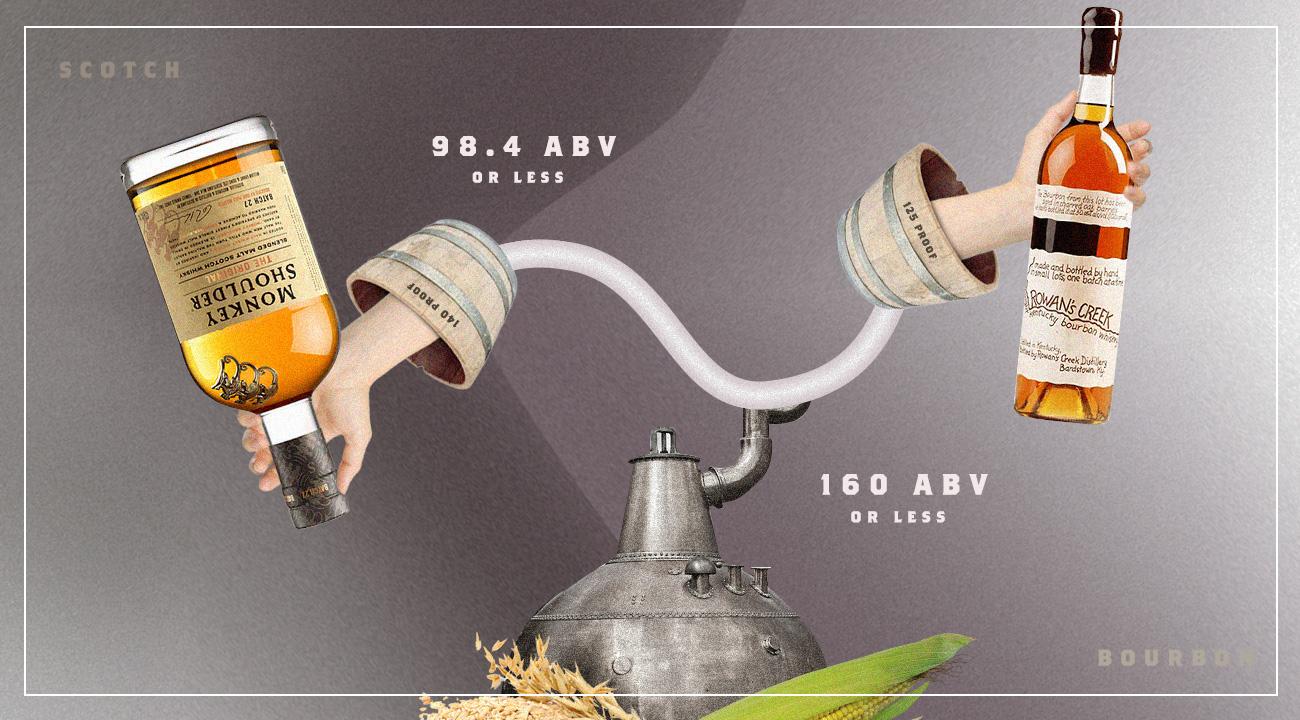

Whether by pot still or column still, Bourbon must be distilled at 160 proof or less, and go into the barrel at 125 proof or less, and be bottled at a minimum 80 proof.

Single-malt Scotch is produced by batch distillation in pot stills coming out at 98.4 ABV or less and often barreled at near 140 proof. Scotch is specified to be bottled at a minimum 80 proof as well.

But before it’s bottled, both Scotch and Bourbon need to sit a spell. To be a legal straight bourbon, it’s got to get comfy in a new, charred oak barrel for a minimum of two years, no additives allowed. The various char and toast levels, the aging time, and even the barrel position on the rickhouse shelves, particularly in the humid south, will all affect the character of the Spirit.

A Scotch must legally be laid to rest for three years, but often spends much more time lounging around in the barrels in cool Scotland. And those barrels might have previously housed sherry, port, beer, and even Bourbon. No new oak—though sometimes it’s re-charred—for those laddies.

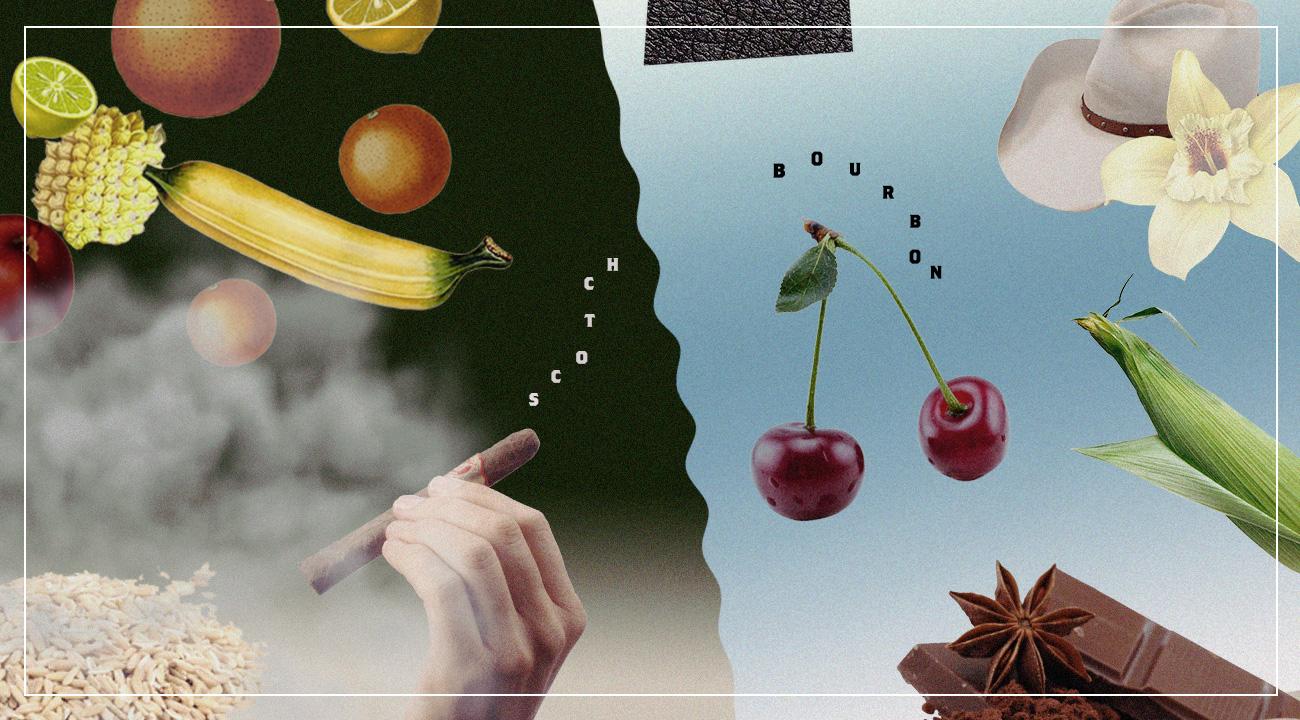

What might you find in your mouth when you tilt a glass of Bourbon? Well, a gamut of flavors that can go from floral to leather to chocolate, but often, maple, vanilla, caramel, and the woody nuances of the oak itself.

Bourbon can have a sweetness not found in many Scotches; all that corn contributes to that confectionary palate.

If we are talking about some of those big-shouldered Islay Scotches, peat and its near-astringent smokiness will clap with both hands on your tongue. But many mainland Scotches, Speyside being a noted source, don’t necessarily rely on big-throated peat for their varied flavors of fruit, flower, or grain.

The blended Spirits in particular have varied profiles (and blends can involve large numbers of varied Scotches): Some blends employ peated single malts and non-peated, some are a mix of malted and non-malted barley, some a grain mix.

Actually, these are all for the home, particularly if you’re sampling more than a couple—safe sipping, folks.

Below are five Scotches and five Bourbons that represent a range of regions and flavor experiences, all of which we can classify as “very good!”

1. Ardbeg Corryvreckan – one of the Islay area, cask-strength peat heavyweights.

2. Balvenie Caribbean – a 14-year-old with a secondary Rum-cask finish.

3. Bruichladdich Classic Laddie – No peat, 100 percent Scottish barley, Bourbon-barrel-aged

4. Macallan #5 – One of the giant names in Scotch, a no-color-but-the-natural-one single malt

5. Monkey Shoulder – A blend of premium Speysides at a compelling price

1. Rowan’s Creek – Kentucky bred, with both manners and muscle, at 100 proof.

2. Woodinville – Washington State knows its Bourbon too, with this secondary-finish-in-port-barrels beauty.

3. Woodford Double Oaked – Woodford has a very old Kentucky home, and this brew went from new oak/heavy char slumber to new oak/deep toast rest—the attention paid off.

4. Larceny – a fine wheated Bourbon at a dandy price.

5. Booker’s “Beaten Biscuits” – A high-proof tasty beast from the Beam family of small-batch bourbons.

Even if they can’t agree on how to spell the stuff, Bourbon folks and Scotch people can agree on this: whiskies make the world a wonderful place. Do check out some of our Flaviar favorites linked above and get some samples into a glass—you won’t be sorry.

Don’t forget that those are just a few of the wide range of Scotches and Bourbons on the site—roam around and see the bounty.

Cheers and Slàinte!