Forget Kentucky! The Mint Julep is a New Orleans Cocktail

|

|

Time to read 6 min

|

|

Time to read 6 min

Some people might raise an eyebrow when I say that the Mint Julep is a quintessential New Orleans drink, simply because they associate the drink so closely with Kentucky. These are people who have probably relegated their julep consumption to Derby Day. But here in New Orleans, we’re happy to sip a julep any day of the year.

Here’s my argument for why we should include the drink in the wider New Orleans canon, besides the fact that many a julep has been consumed here, both today and for hundreds of years: First, the spirit we all associate with the drink, Kentucky’s signature, bourbon, is a relative newcomer on the julep scene. For most of its time on earth, the julep was not made with whiskey; it was made first with rum, then brandy. The word “julep” is centuries old and derived from the Persian word for rose water, gûl-ab. In its original, medieval-English iteration, a julep was a medicinal concoction of herbs, sweetener, and maybe a little booze. But according to David Wondrich, once it made its way to Virginia in the late 1700s, the julep shed its pharmaceutical trappings and was embraced for what it truly is: a boozy party in a glass.

Notably, those colonial Virginians were making their juleps with rum. According to Stanley Clisby Arthur, early New Orleanians were drinking their juleps with rum, too: His book features a recipe for the San Domingo Julep, made with rum, loaf sugar, and mint, and suggests that it is “the original mint julep that came to Louisiana away back in 1793,” brought to port by plantation owners and aristocrats fleeing the slave rebellion in Haiti. (Of course, Arthur offers no citations or evidence to back up this claim. We should never take his word as gospel.) By the early 1800s, Americans had developed a taste for imported French brandy, and more of them had the means to pay for it. So cognac became the fashionable choice for juleps. We know how much nineteenth-century New Orleanians loved their fancy European products—absinthe and anisettes, Madeira, sherry, and the like—so it seems pretty likely that they would have jumped on the brandy-julep bandwagon. From there, a few regional spin-offs started popping up: In Georgia, South Carolina, and other peach-producing states, peach brandy proliferated in the mid-1800s, resulting in a tasty regional julep. It wasn’t until well into the nineteenth century, when phylloxera wiped out the global brandy supply, that American whiskey really came into play at all.

If the base spirit is changeable, then what really makes a julep a julep? The mint, sure. But for me, it’s the ice. A well-made Mint Julep is recognizable from a mile away. When you see that frosted glass with the dome of crushed ice peeking over the top, an abundant bouquet of fresh mint drilling down through its surface, you know the drink could be only one thing. Sometimes I like to imagine those early-nineteenth-century Americans ordering their first Mint Julep. When that drink landed on the bar—when they saw that bounty of clear, cold, beautiful ice—my guess is they went totally apeshit. We take ice for granted, but it was such a luxury back then—especially in tropical climates like Louisiana, where any ice you tasted was lake-cut in the North and transported via cargo ship down the Mississippi. On those 90- to 100-degree days of New Orleans summer, you must have been so grateful for anything that made it into your glass still frozen.

So now, just imagine receiving a tasty cup of sweetened, aromatic liquor in a silver or pewter cup that is overflowing with so much glorious ice that the exterior is frozen, almost painful to hold in your hands. It must have been such a power move to order a Mint Julep. It wasn’t “Give me your most expensive bottle of wine,” but rather, “Give me your cocktail with the most ice.”

It is notable but unsurprising to me that the first large-scale mechanical ice manufacturing facility in the United States—some say the world—opened in New Orleans in 1868. By that time, there were several ice storage facilities throughout the city. But when blockades during the Civil War cut off the supply to precious lake-cut Northern ice, intrepid New Orleanians decided to engineer a solution. The Louisiana Ice Co. took water from the Mississippi, distilled it, and, through steam-powered machinery, converted it into ice. “The manufacture of artificial ice, at the works, is particularly attractive to the looker-on, from the fact that the operation, from the pumping of the water from the turbid river, near at hand, to the slipping out of the polished, glistening slabs of alabaster-looking ice from the tin moulds, in which they are congealed, is so excessively simple and clean,” wrote the Picayune upon the factory’s opening.

I have found no evidence to suggest that the owners of the Louisiana Ice Co. were Mint Julep enthusiasts, but it doesn’t seem like that much of a stretch to imagine they were. I did find newspaper articles from the era bemoaning how ice shortages would affect Louisianans’ ability to enjoy their beloved julep: “The connaisseurs [sic] in good beverages and lovers of iced mint-juleps, are wondering with a heavy sigh if enough energy is left here to insure us in having ice this season. The time for such is at hand, and as yet we have not received our first hint of the Spring nectars.

Who is going to move in the matter?” opined the Louisiana Democrat in April 1875. My recipe calls for bourbon, because that’s what people have come to expect from their juleps. But rum or brandy wouldn’t be out of place at all. The only nonnegotiable in my mind is that you must fill your glass with an overabundance of ice. At our bars, we use pellet ice from our Scotsman machine; at home, you should crack your own ice. Add the ice to the serving glass (a julep cup is traditional but not necessary) in stages, agitating it by stirring or swizzling after each addition so it starts to melt and dilute what would otherwise just be a sweetened shot of hooch.

As you sip your icy-cold julep from a straw, close your eyes and imagine a world without air-conditioning, without refrigeration—a hot, sticky world where people rarely bathed and the smell of summer was enough to knock you dead. Stick your nose in the bouquet of mint, maybe graze that heaping mound of ice. Inhale. Is this not the best drink you’ve ever had?

The spec below is very traditional and very basic. So technique is important here. Despite what you may have been told, you should not “muddle” the mint. If you pulverize it, you’ll extract bitter and unpleasant flavors from the chlorophyll. Instead, gently press the mint with the back of your barspoon against the glass. Do not “slap” the bouquet you’ll use for garnish. Just gently brush it against the back of your hand; that’s enough to activate the aromas. Add the ice in stages and agitate (swizzle or stir) at each step. Purists may scoff, but I like to add a dash or two of Angostura to my Mint Juleps. Pretty much everything tastes better with bitters.

2.25 oz (67.5 ml) Buffalo Trace Bourbon

.5 oz (15 ml) Demerara Syrup (recipe follows)

12 mint leaves, plus 1 bouquet for garnish

Combine all the ingredients except the garnish in a julep cup and stir to combine, making sure to gently press the mint leaves against the sides of the cup with your barspoon. Fill the glass halfway with crushed ice, then stir to agitate and dilute the whiskey. The proof of the whiskey should melt the ice pretty quickly, which is what you want—this drink needs dilution. Add more crushed ice to fill the cup again, then stir again to agitate. Refill the cup with more ice, stir one last time, then add enough crushed ice so it mounds over the edge of the julep cup, which should be frosted over by now. Brush the tops of the mint bouquet against the back of your hand to activate the aromas, then place the bouquet in the drink to garnish it. Serve with a straw.

2 parts Demerara sugar

1 part water

Combine the sugar and water in a small saucepan and bring to a boil. At the first crack of a boil, remove from the heat and continue stirring until dissolved. Let cool then transfer to a nonreactive container. Store airtight in the refrigerator for up to 4 weeks.

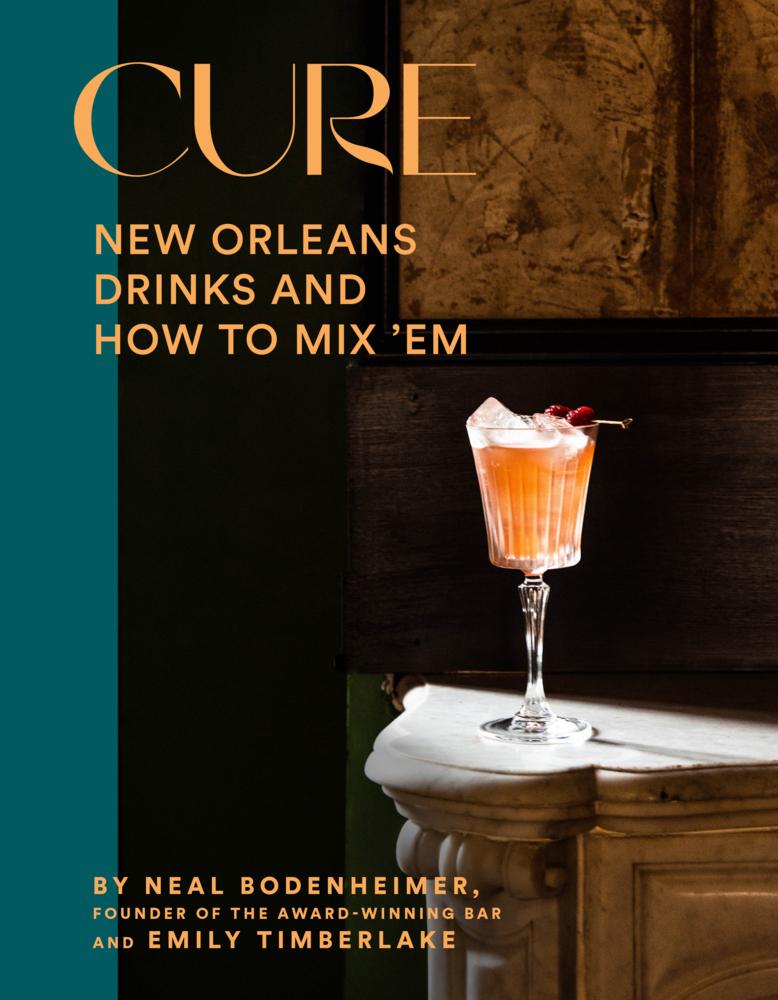

Excerpt from the new book Cure: New Orleans Drinks and How to Mix ‘Em by Neal Bodenheimer and Emily Timberlake, Published by Abrams. Photography © 2022 by Denny Culbert.