Tequila Cocktails Before the Margarita

|

|

Time to read 8 min

|

|

Time to read 8 min

There were Tequila cocktails before the Margarita, and popular ones, too. But in 1953, when the Margarita first stumbled into print after a decade and a half of scrabbling around the borderlands between Mexico and the United States, it promptly took off like one of the Air Force’s new ballistic missiles, in the process drawing a line through the whole category of Tequila drinks with its contrail. On one side stood the Margarita and the future. On the other—prehistory. In no time at all, its former peers became the sort of quaint, rough-draft concoctions that are doomed to be fast forgotten and forever unrevived.

To be honest, prehistory is where most of those early Tequila cocktails probably belong. The first one on record, though, is pretty solid: that came to notice in 1883, when “Rambler,” a correspondent for the Las Vegas, New Mexico Daily Gazette observed that “tequillo [sic], when made into a cocktail, the same as american whisky [sic] is mixed, makes a pleasing drink.” Seeing as American Whiskey was made into a cocktail back then by mixing it with bitters, sugar and ice, anybody who has enjoyed Phil Ward’s modern-classic Oaxaca Old-Fashioned will concur with Rambler’s opinion. Add the Mezcal cocktails being served in San Antonio, Texas, and the simple Tequila Punches and Fizzes here and there in Mexico City and you’ve got a more than promising early start.

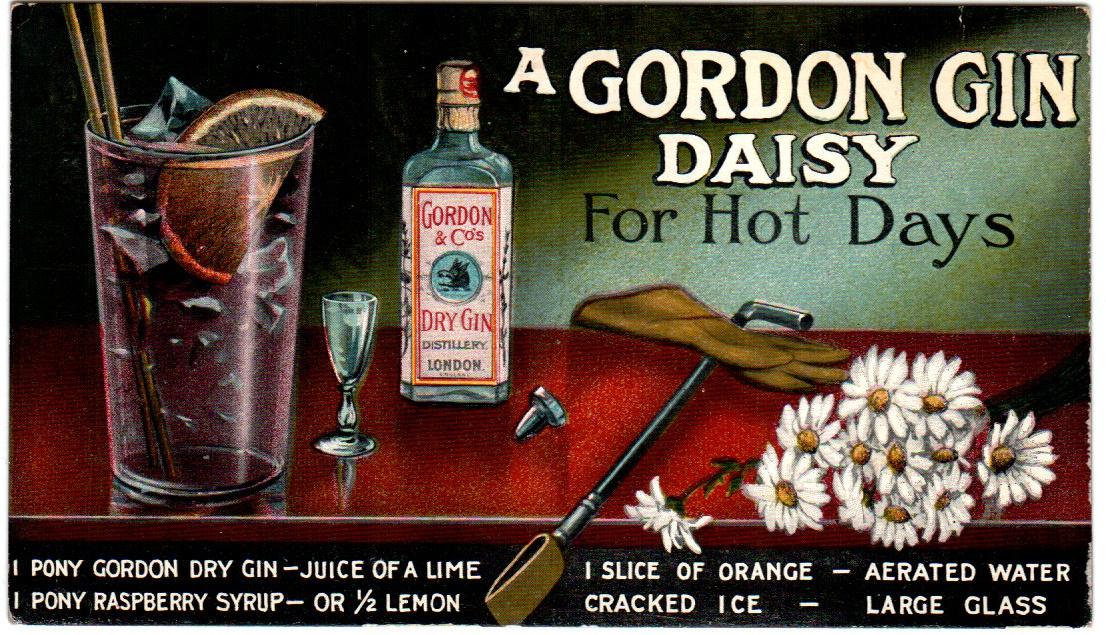

Then things got a little odd. The oddness started in the borderland, where you could find both Tequila and American cocktail-drinkers. One day in 1925, give or take a year, one of those drinkers asked the bartender at the popular Turf Bar in Tijuana for a Gin Daisy. Normally, that would be a mix of Gin and lime juice with something red and sweet—raspberry syrup was original but grenadine was cheaper and that’s what almost everybody used—and a healthy splash of soda water, served on the rocks in a big glass. (There was another, earlier Daisy, made with booze, lemon and orange liqueur, but that belongs to the history of the Margarita itself.)

But Henry Madden, the forty-something year old Kansan who was behind the bar, grabbed the wrong bottle, and instead of a Gin Daisy he made a Tequila Daisy. No big deal—in fact, as Madden later recalled, “the customer was so delighted that he called for another and spread the good news far and wide.” Before long, the bar was sporting a big sign proclaiming it the “Home of the Famous Tequila Daisy”; once Repeal rolled around, it took out ads in the San Diego papers making the same claim.

By the 1940s, the Tequila Daisy had spread up the west coast to Los Angeles, down to Ensenada and then along the border through Mexicali, Nogales, and El Paso/Juarez all the way to the Gulf coast. It was talked about in books, namechecked in Time magazine, called out in Tequila ads. (America’s entry into World War II led to a serious Whiskey shortage and a spike in Tequila imports.) The Tequila Daisy was a known drink. And yet—and this is one of the oddities—nobody thought to publish an actual recipe for the drink until 1958, other than the garbled ones that collectors have turned up in a pair of throwaway 1930s Mexican liquor-store brochures. It made it into no bartender’s guide, no known newspaper article, no travel guide or book of Mexican cuisine. Nobody ever even thought to mention just what was in the thing.

Judging by the 1958 recipe, which seems to jibe with the limited early descriptions we have of the drink, you can see why the Tequila Daisy made it as far as it did, passing from bartender to bartender, drinker to drinker. It was smooth, pleasant and colorful, and cheap and easy to make. A modern critic might say that it lacked complexity, but no matter; it established the principles of tequila mixology for a generation: 1) Make It Sweet; 2) Make It Sour; 3) Make the Drink Pink; 4) Don’t Forget the Grenadine.

Those principles were all in action in the next Tequila drink to gain popularity, also in the borderlands. The Tequila Sunrise, an invention of the gold-tiled bar at the Agua Caliente racetrack-hotel-resort in Tijuana, supplemented the tequila-lime-grenadine triad with a key splash of crème de cassis and an extra-large glug of soda water. (There was no orange juice in it; that was added in 1970 by a young Sausalito bartender who hated following recipes).

Sometime in the 1930s, the new, Daisy-based Tequila-grenadine mixology opened another front, this one in Mexico’s capital and a couple of resort towns nearby. By then, Mexico City could boast of a clutch of new, modern cocktail lounges, including El Patio, La Cucaracha, Zandam, the California Buffet, Bottoms Up, and the bar at the Hotel Prado. Unlike the places serving American drinks there in previous generations, these were staffed by Mexicans and catered primarily, but not exclusively, to a Mexican clientele. Upscale and stylish, they mostly served the same drinks you would get in New York, London or Paris—anywhere, in short, where the American art of the bar had taken root. Martinis, Manhattans, Sours, Sidecars, Stingers, like that. But there was a little clutch of Tequila drinks that they shared between them that was unique to Mexico City. There were the Sunrise and the Daisy—according to surviving menus, a bar would have one or the other, but not both. Most also featured the Tequila Cocktail, which was nothing more than a Daisy with a dash of absinthe or substitute and no soda water, and the Pancho Villa, which substituted Sweet Vermouth for the lime juice and added a few drops of vanilla and, of course, a squirt of Grenadine. The Tequila Especial kept the lime and added pineapple juice, but switched to another red product, Cherry Brandy, for the Grenadine. At least the result was still pink.

I’ve tried the Tequila Cocktail, the Pancho Villa, and the Tequila Especial. There’s nothing really wrong with any of ‘em (OK, maybe the Pancho Villa). But they represent baby steps, the first attempts by Mexican bartenders to plug Tequila into the gringo school of mixed drinking. They’re not bad, but things would get better.

Ironically, the best pre-Margarita Tequila drink I’ve been able to find, besides, of course, the various Margarita precursors (some of them Margaritas in all but name), comes not from the borderland or Mexico City, but rather from the heart of Greenwich Village.

El Chico was New York’s most authentic and probably best-loved Latin nightclub for 40 years. It was opened in 1925 by Benito Carreno Collada, a young Spaniard from Asturias who had worked his way up to bell captain at New York’s iconic Hotel Astor before he was 20 and then traveled Europe and Latin America for Thomas Cooke, the company that invented the tour group. In 1930, Collada moved the club to the new building at 80 Grove Street, right on Sheridan Square in the heart of the West Village. The club’s focus was its very authentic Spanish singers and dancers (Collada went back to Spain every summer to scout new talent) and its somewhat less authentic Spanish-American food, but once it became legal to do so, it also boasted of its Spanish Wines; the Malagas, Riojas, and such that Collada collected on his trips.

With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Collada had to give up his annual Spanish scouting missions. Instead, he would head south, and before long the club’s musical acts took on a decided Latin American cast. Mexico, in particular, proved a fertile source of talent. But singers and flamenco dancers weren’t the only thing he brought back: he also started serving Tequila drinks.

Now, El Chico didn’t have an actual, honest-to-goodness bar, not until 1945. The Daiquiris, Mojiotos, Cuba Libres, Presidentes and such that it generally served all came out from a service bar, and we’ve got no idea who stood behind that. But whoever was running the bar seems to have been down to Mexico City, since a 1941 drinks list for the club has our old friends the Tequila Cocktail and the Tequila Especial.

But it also has a “Gay Caballero” (a Cesar Romero western of the same name had come out in 1940), and this one breaks all the Tequila-drink rules. Well, OK, half the rules: it’s sweet and sour, but it ain’t got no grenadine and it ain’t pink.

What it is is a sophisticated mixture of Tequila and Málaga wine—a sort of cousin to Sherry—with citrus juice, orange Curaçao and maraschino liqueur, garnished with a twist of orange peel. It sounds unlikely, and it took a little tinkering with proportions (the menu description, the only documentation we have of the drink, lists ingredients but not how much of each) to get it to come out right, but the result is a nicely complex drink where the tequila gives it intrigue without taking over; where it leads the chorus, so to speak, rather than singing a solo with distant accompaniment. This is a trick many modern mixologists have yet to master. If this is prehistory, then call me prehistoric.

El Chico, New York, 1941

Glass: Cocktail

Garnish: Orange Peel

Add all of the ingredients to a shaker and fill with ice. Shake, and strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Twist an orange peel over the top and discard.

And, just because it’s a nice, cheerful drink:

Henry Madden, Turf Club Bar, Tijuana, ca. 1925

Glass: Cocktail

Add all of the ingredients, except the sparkling water, to a shaker and fill with ice. Shake, and strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Top with sparkling water, or as much of it as will fit comfortably in your cocktail glass.

Finally, a note on the Gay Caballero’s name. Yes, by 1941 “gay” was already slang for, well, gay, at least in the gay community. And El Chico was right there on Sheridan Square, less than 100 feet from the Stonewall Inn where the gay liberation movement would start a generation later. Even in 1941, the West Village had more than its share of gay residents, but it was not yet the center of the (then mostly closeted) community. In other words, did El Chico mean anything funny by the name? Could be, but probably not.