The Deep Dive: When Is a Classic Cocktail Not a Classic?

|

|

Time to read 19 min

|

|

Time to read 19 min

A quick riffle in the stream of time and it’s 1939, you’re in New York, and you need a drink. And why look! That’s the Commodore Hotel, right there, and everybody knows the Commodore has a great bar. You snake your way through the bustling lobby, doff your hat—of course you’re wearing a hat; everybody is—and step into the cool, dark barroom. The bar is long and ornate, decked out with…who cares—here’s the bartender!

“What will it be, sir?” He’s wearing a little red jacket and a black bowtie, but it doesn’t make him look silly. It makes him look professional.

“Well, I’m in New York, so it’s gotta be a New York Sour, right?” He gives you a look.

“I’m afraid I don’t know that one, sir. If you—” So maybe not so professional.

“Okay, no worries. Make it a Boulevardier.” Again with the look.

“So not a Boulevardier.” Too French? Who knows, but probably best to order something super-classic. “Let’s just make it a Last Word, then.”

“Look, pal, I don’t know where you’re used to doing your drinking, but it ain’t around here.” With that, he hands you a little white booklet. “Here’s what we drink at the Commodore bar, on 42nd Street in New York City, U.S.A.”

As a collector of old cocktail menus, I’ve long noticed that a surprising number of the drinks that we consider top-rank classics—drinks that have stood the test of time and are a part of a bartender’s essential knowledge—are nowhere to be found on those menus. In fact, upon investigation, it turns out that when those particular top-rank classics—including the Jungle Bird, the Aviation, the Corpse Reviver No. 2, the Saturn, the Hanky Panky, the Pegu Club and the Blood and Sand—were new, almost nobody served them, ordered them, drank them or had even heard of them. It’s only in recent years, with the modern cocktail renaissance, that they’ve been given their star turn.

I got to thinking about them again a few weeks back when I found myself at FIBAR (that’s with an “I”), Spain’s annual bar show, listening to a talk by cocktail critic Robert Simonson about “modern classic” cocktails, the subject of his recent book of the same name. Were these newly popular old drinks old, classic classics or modern ones? And what should we call them? When the time for questions came, I raised my hand and we kicked the topic around a bit. Simonson seemed intrigued, but he didn’t have a detailed answer any more than I did, nor did either one of us have a good name for them. When Noah Rothbaum and I had him on our podcast, Fix Me a Drink, to discuss it, we were able to get more deeply into the details.

But although we managed to establish who resurrected the Jungle Bird and things like that, we still didn’t come up with a satisfactory name for the drinks as a category. Nor did we have time to get into the thing that really interests me about them, and that’s the why of it; the reason these particular formulae became more than just a handful of old recipes.

These drinks certainly have something to teach us about how drinks get famous and are well worth discussing, but it turns out they’re the only tip of the iceberg, and there’s no point talking about the tip without talking about the rest of the berg. That iceberg is our canon of classic cocktails—the list of old drinks every bartender is presumed to know and every barfly to know of—and how it relates to what people were drinking back in the day.

“Classic cocktail” can mean a lot of things. It can be shorthand for any drink from back when bartenders wore red jackets and knew how to mix drinks. Generally, however, there’s an implication that a classic cocktail stands somehow apart from the vast army of recipes that are preserved in the pages of old cocktail books like so many Qin-Dynasty terracotta warriors, patiently waiting beneath the earth for a shot at glory. The true classics were never buried. They’re the drinks that were famous in their day and are on display in old movies and novels, photographs, paintings, what-have-you. The drinks that became part of larger pop culture. Many of them never stopped being served no matter what was going on in the world of drinks and the others died hard.

It’s never easy to compile a list of these things, and not just because the boundaries of any canon, whether it’s of Greek lyric poetry, English Pre-Raphaelite painting, or Yu-Gi-Oh cards, are going to be porous and hard to fix. With cocktails, canons have generally been drawn up impressionistically, based on the drinks that pop up most often in old cocktail books, plus any others that seem to have been important or—always a problem with doing things this way—of which the compiler is particularly fond.

Rather than try to draw up my own canon, I’d rather go back to where this whole thing started for me, the menus. Cocktail books give you all the drinks that the author thought might be served. Just for once, why not instead go with what was actually served? Like, say, what they were mixing up at fancy New York hotel bars in 1940 or thereabouts? New York, because the city not only has long had a long and friendly relationship with the cocktail (if the cocktail had a capitol, it would be Manhattan), but it also has had a way of absorbing the best drinks from all over the country—the world—and making them its own. Hotel bars, because they’re generally high-volume bars that avoid being too weird or geeky; after all, they have to accommodate people of all kinds, often all at the same time. 1940, because it’s long enough after Repeal for the disruption brought by Prohibition to have begun to heal, but still before the U.S. entered World War II, which would bring its own disruption. This period was the Indian Summer of the great Golden Age of the cocktail, which stretched from the end of the Civil War to the beginning of World War II.

You could equally choose another place or another time: you’d get rather different, more regionally-focused lists from, say, San Francisco, New Orleans, Paris, London or Havana, or from 1970, 1960, 1950 or 1920—although that last one would be tough, since American cocktail lists were almost never printed before the 1930s and European ones were rare.

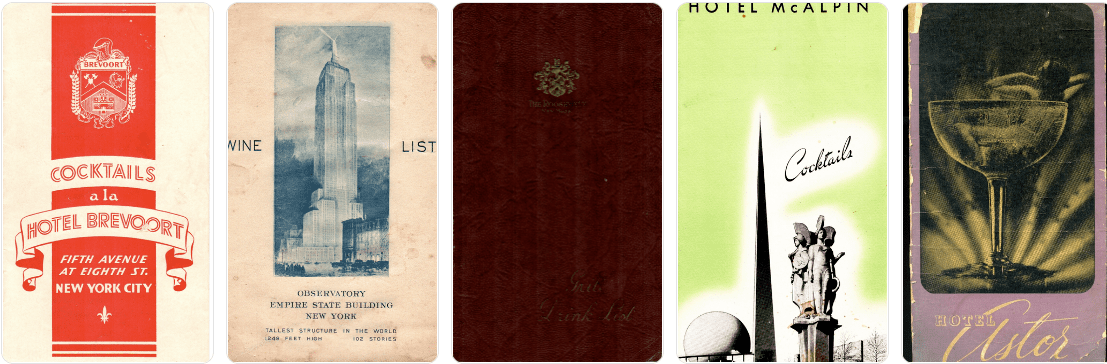

In favor of New York, 1940, on the other hand, is the practical reason that, thanks to procrastination, eBay, and online menu collections, I’ve been able to amass at least a dozen cocktail menus from New York bars from the period, including several from the great hotels. That means I could pick out five nice, extensive hotel lists to study, all from 1938-1941. Five is enough to give us a good sample but not so many as to be unwieldy, and there are still several others in reserve against which we can check any conclusions.

The lists I chose are from the Astor, in Times Square; the Commodore, on 42nd St just east of Grand Central Station; the McAlpin, in Herald Square; the New Yorker, on 8th Ave at 34th St; and the Roosevelt, at Madison Ave and 45th St. These were all big, prominent hotels with well-known bars. (All but the Astor are still standing, under one name or another, although in 1978 a local developer named Donald Trump had the Commodore’s classic façade stripped off and replaced by a steel and glass skin; now it’s called the Grand Hyatt.)

If you take all the cocktails and other mixed drinks on all five menus—the numbers range from 46, at both the McAlpin and the New Yorker, to 83, at the Astor, for an average of 59 drinks—and collate them, you find a remarkable amount of overlap. 20 drinks, roughly a third of that average, were served by all five hotels. They include such got-to-be-theres as the Martini, the Manhattan and the Old-Fashioned, of course, along with such steady supporting players as the Sidecar, the Tom Collins, and the Jack Rose.

But 20 drinks are just not enough for a proper canon: there are a number of drinks that aren’t on the list and, judging from what got talked about in gossip columns and such, should be. That suggests that limiting our canon to drinks that all five hotels had on their lists is rather too strict. If we say a drink has to be on at least four out of five lists, that gives us another 14 drinks, while a three-out-of-five standard gives us another ten beyond that, bringing the total up to 44 drinks and, more importantly, roping in the Sazerac. A canon of classic cocktails without a Sazerac in it is too sad to contemplate, and hey, three out of five is still a majority. Besides, all but two of those last drinks appear on other New York lists in my little collection, and the exceptions are well attested to in contemporary cocktail books.

So. Here’s the list; the drinks that were considered classic, back at the culmination of the first classic-cocktail era:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This of course still leaves a few things out: for one thing, it omits a couple of winter drinks—the Hot Toddy, Tom & Jerry—that were just as established as any of these. Plus, as with any canon, there was a lot of activity around the edges. Looking at other drinks menus from the time, there’s a remarkable degree of agreement with our canon, but some drinks—the Singapore Sling, the Gibson, the Ward Eight—do turn up often enough to suggest that, with a bigger sample, they would have made it onto our list. Other pedigreed drinks were if not canonical, then at least canon-adjacent: e.g., the Paradise, with gin and apricot brandy. There were also the fads, from the Southern Comfort-based Scarlett O’Hara to the Tequila Daisy, with stops at the Zombie, the Gin & Tonic, the Bloody Mary (which first made it into print in 1939) and the Vodka Martini. But again, canons are generally fuzzy around the edges, and this still gives us a very solid picture of what was a classic during the first Golden Age of American drinking.

Comparing apples to apples, New York hotel-bar lists to New York hotel-bar lists, the canon remained remarkably stable all the way into the 1960s. Sure, a couple of drinks got added and the prices more or less doubled, but there was little on a list such as the one the Hotel Manhattan was using in 1961 that would have challenged a bartender from 1941. Of the 20 drinks the hotel offered, only the Screwdriver and the Vodka Tonic weren’t on any of our 1940 lists, while 16 of the drinks were on our three-out-of-five list. The New Yorker’s 1957 list had just 18 drinks, all but five of which were on the three-out-of-five and only the Vodka Tonic was entirely new. It’s the very shortness of these lists, though, that tells us what was actually happening. In the 1950s and 1960s, the drinks a bartender was expected to know; the drinks that people actually came in and ordered, were getting fewer and fewer. Things that once seemed classic and timeless suddenly seemed old-fashioned, fit only for old fuddy-duddies.

I don’t know which drinks were the first to fall, but one thing conspicuously absent from the Hotel Manhattan’s list and others of the time are egg drinks. That means 86ing not just the whole-egg drinks and egg-yolk drinks—so the Coffee Cocktail, the Sherry Flip and Fizzes Royal and Golden—but even the egg white drinks, like the Clover Club and Silver Fizz.

A bunch of others followed, for one reason or another: the Jack Rose, the Pink Lady and its near-identical twin the Royal Smile all had applejack in them, and nobody seemed much interested in that. Various other brandy and wine drinks joined them in exile, although as a consolation prize brandy got to take over the Alexander from gin, and thus be mixed with crème de cacao and heavy cream.

The Whiskey Rickey fell, dragging the Gin Rickey down with it. The Horse’s Neck (soda water with a loooong curl of lemon peel) got put out to pasture with the Lone Tree (a sweet-vermouth Martini), probably in the Bronx. Even the mighty Bacardi Cocktail (simply a Daiquiri with grenadine instead of the sugar) sailed off into the sunset, while the Mint Julep, America’s first drink creation, was cut back to one day a year. As the 1960s wore into the 1970s, only some 12-15 drinks of our original 44 were left in the repertoires of those bartenders who still bothered to learn their classic cocktails (there were plenty who found it entirely unnecessary).

But there were additions, too. Even as the canon was shrinking, there were still drinks that traveled around enough, won enough fans, and managed to stick around long enough to become canonical. They include such essentials as the Margarita, the Bloody Mary, the French 75, the Irish Coffee, the Mai Tai, the Gimlet (thanks to Philip Marlowe and his creator Raymond Chandler) and I suppose even the Piña Colada.

By 1980 or thereabouts, if you could find a bar that specialized only in classic cocktails, its list would look a lot like this (the newcomers are marked with an asterisk):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here, however, I’ve had to rely on memory and educated guesswork, because, of course, in 1980 there pretty much weren’t any bars that specialized only in classics, at least not in America. Sure, a joint like P. L. Cahoots in Frederick, Maryland—which offered a list of 170 drinks, every one of them Shooters and most of them original, including the Body Odor, the Horny Moose, the Training Bra and the South Bronx (when is a Bronx not a Bronx?)—was maybe a bit of an outlier. But even the Oak Bar at the Plaza Hotel was serving far more Cape Codders and Godfathers than it was Sidecars or Sazeracs.

Then came the cocktail renaissance—and, some would say, it was about time, too.

By the time the bloody 20th century was skidding into the homestretch, there was quite a passel of people whom twenty-plus years of heavily-promoted “fun” drinks had left deeply unimpressed; people who didn’t care much for Long Island Iced Teas, Woo-Woos or Appletinis, let alone Fuzzy Navels, Body Odors or Horny Meese—or whatever the hell the plural of “moose” is. Some of them were bartenders. Beginning in the late 1980s, Dale DeGroff, Dick Bradsell, Murray Stenson, Paul Harrington and a handful of others began to find that whenever they reached back into the repertoire and made French 75s, Stingers, Sazeracs and the like, their customers really liked it, and not just the crusty “gin-Martini, up” drinkers, either. A little, and in DeGroff’s case not-so-little buzz began to surround them.

What’s more, by the late 1990s, the Internet was here. That made it much, much easier to amplify any such buzz. Suddenly, isolated cocktail traditionalists, the sort who went to the 21 Club for the Southsides and Musso & Frank’s for the Jack Roses, found themselves members of a clique, which quickly became a community, and then a movement, dedicated to reviving the classic cocktail and with it the traditional American art of the bar.

But while there was a lot of interest in classic cocktails, there wasn’t a lot of agreement as to what exactly constituted a classic. The 1980s version of the canon wouldn’t do: it included a lot of drinks that, while authentically old and popular, sailed too close to the type of mixology the movement was trying to get away from: too sweet, too weak, too creamy, too frivolous.

It wasn’t just that the new traditionalists had spent the past generation confining their drinking mostly to ultra-dry gin Martinis and Scotch on the rocks and were used to tasting the booze, although that was surely a factor. But this was more than a matter of personal taste. It was a movement, and movements need focus. There needed to be a clear line of demarcation between the supposedly corrupt, degraded and decadent modern way of mixing drinks and the way they did it in the Golden Age, whenever that was. (Before Prohibition? During Prohibition? The Art Deco era? Whenever the Stork Club was popular?) Drinks such as the Grasshopper, the Sloe Gin Fizz, the Singapore Sling (particularly after its juice-heavy early-1970s revamp), the Cuba Libre, the Piña Colada, the Planter’s Punch, Kir (with Champagne or without) might have been legitimate classics, but they blurred the line.

So of course did the Vodka Martini, a drink that went back to the 1930s and had been enormously popular for two generations. In 2003, when Esquire magazine launched their first drink book since the 1980s, it was at “Esquire’s First Real Martini Invitational,” a Martini-mixing contest. The only rule? “A real Martini consists of gin and vermouth, period.”

Shadowbanning these drinks, however, as essentially happened, left a pretty sterile canon; one where all the drinks are not just well known, but very, very well known. That’s no good—every canon needs a few wild cards in it to make things interesting. Imagine the British Invasion with the Beatles, Stones and Who, but not the Kinks or the Animals. I mean, no Gerry and the Pacemakers, ok. I could probably survive without “Ferry Cross the Mersey,” although only just. But with no “House of the Rising Sun” or “Waterloo Sunset,” life would have no meaning.

In other words, the movement needed some more classic cocktails. They couldn’t be new drinks, either: the “craft cocktail” movement, as it became known after Dale DeGroff published his groundbreaking book, The Craft of the Cocktail, had as its selling point that it was just restoring what had always been there. What was needed were new old drinks, so to speak.

Needless to say, none of this involved conscious planning. If there had been such a plan, a committee would have collated a gang of old cocktail menus, figured out what the canon used to be, and started paying bartenders to learn all the forgotten drinks. Everything would have come crashing down when the first Sherry Flip got placed on a coaster.

People didn’t want to drink like it was 1940; they wanted to drink like it was 2000, but with more (old, boozy and delightful) cocktails like the ones they already loved. And that’s what they got.

Let’s get back to our buried terracotta army; to the dusty old cocktail books and the legions of recipes they contain. Their number is vast. In the 1930s, one R. de Fleury published 1700 Cocktails for the Man Behind the Bar, following it up three years later with 1800 and All That, with that many more recipes. That’s 3,500 different recipes—and that was just one writer. The vast majority of these recipes never amounted to much, although it’s not necessarily a case of Sturgeon’s Law, which states that 90% of everything is crap. It’s safe to say that most of these recipes are at least ok; they’re just not distinctive.

Between 1995 and 2010, give or take, bartenders, drinks writers and the like sank a great deal of effort into archeology; into finding the books where those recipes had been collected and mining them for anything that could be dusted off, spruced up and sent to serve on cocktail lists next to the house versions of the Manhattan, the Daiquiri and the Old-Fashioned.

What we were looking for—I can say “we” here because at the very end of 1999 I was hired to produce a database of old drinks for Esquire magazine, which rapidly led to a job as their drinks columnist—wasn’t what had been the most popular drinks or even necessarily the best ones.

We wanted drinks that seemed, to us in 2003 or thereabouts, timeless: as simple, delicious and distinctive as the Sidecar and the Rob Roy. All too often, though, that translated into drinks that had a secret-handshake factor; that immediately identified whoever served them as a member of the movement. That could be the use of rare, archaic ingredients such as gin or rye (both endangered), maraschino liqueur, Chartreuse and Italian bitters. Even the use of a forgotten technique or piece of bar gear that made a bartender look slick (in some parts of the country, that could include something as basic as stirring) signified that you were a club member.

In any case, most of these drinks were quietly replaced the next time the menu was changed. But every once in a while one of them spread beyond the bar that had first resuscitated it and actually caught on. Some of these drinks had been in the 1940 canon and were merely reclaiming their seats, with the help of one or another contemporary bartender or journalist. Thus Sasha Petraske, at New York’s Milk and Honey, brought the Gin Daisy and the Silver Fizz, egg white and all, back to the table, while a cabal of Boston bartenders (including Jackson Cannon, Misty Kalkofen, John Gertsen and the late and much lamented Brother Cleve), made up the Jack Rose Society, dedicated to the propagation of that drink and other classics, while Derek Brown and some other Washington, DC bartenders did something similar for the Gin Rickey, originally a DC drink.

But now sitting beside these legitimate classics were a double handful of drinks that were looking around with puzzlement at the company they were keeping. The members-only Detroit Athletic Club had carried the Last Word on its cocktail list from 1916 into the 1950s, but it had not traveled beyond the club’s doors until Murray Stenson pulled it out of Ted Saucier’s 1951 Bottoms Up, the only place it had ever appeared in print, and started serving his take on it at Seattle’s Zig Zag Café. It ticked off a lot of secret-handshake boxes. Three of the four ingredients—gin, maraschino liqueur, green Chartreuse and lime juice—were uncommon, its pedigree was firmly established, it was plenty boozy, and it had Murray, the Dean of West Coast bartenders, behind it.

The Last Word got its seat right away. Other drinks had to wait awhile. In 2003, when bartenders Dushan Zaric and Jason Kosmas put the New York Sour (a whiskey sour with a tasty and visually-appealing red wine float) on the list at Schiller’s Liquor Bar on New York’s Lower East Side, it didn’t do much, although the splash of orange juice they added has stuck with it ever since. Only after Julie Reiner started serving the drink at Clover Club in Brooklyn, some five years later, did it rise to near-ubiquity. By then, there were iPhones and social media, and extraordinary good looks were a positive asset for a drink.

Or take the Boulevardier, a bourbon Negroni. Between 1927, when it first saw print in Barflies and Cocktails, a special edition of the little bar book put out periodically by Harry’s New York Bar in Paris, and 2008, when Greg Boehm and I put out a facsimile of that booklet under the aegis of his Mud Puddle Books, not a single mention of the drink has been found. It was as dead as a doornail. In 2009, the drink made it into popular drink books by Ted Haigh and Jason Wilson, but it still wasn’t until the mid-2010s that it took off. By then, of course, both the Negroni and bourbon whiskey had become items of cult worship.

I’ve long believed that drinks don’t become truly popular unless they fill a need—and I don’t mean an industry need (if that were the case we’d all be drinking blended Scotch and Canadian whisky cocktails). It helps, of course, if they have a well-known advocate, but that’s not sufficient, nor is it always necessary: the Blood and Sand, for instance, made it to the table without anyone’s hand on its shoulder. (There was a need for a Scotch cocktail to fly wingman for the Rob Roy, and it had the pedigree, coming as it did from the Savoy Cocktail Book. It didn’t hurt that it had a good name, something that Mr. Simonson has identified as a qualifier for classic status.) Each of these drinks filled a need that wasn’t there, or that was otherwise satisfied, back when they were first invented.

That fact suggests what we can call them. In the U.S. Army, when an enlisted person is promoted from the ranks to replace an officer who has fallen in battle, they’re known as a “mustang.” And what are these drinks if not mustang classics, promoted from the ranks to make up for losses incurred? In the army, the mustangs often turn out to be the most vigorous, effective and popular officers. Is it the same with cocktails? That’s something we’ll need to settle over drinks.

Finally, here for the sake of argument is a purely subjective guess at what the classic cocktail canon might have looked like right before Covid scrambled everything up. If you’d beg to differ, come find me at the bar and we’ll talk about it; I’ll be the one drinking a New York Sour.

Classic Cocktails ca. 2020 (50 Drinks); mustangs are marked with an asterisk.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|